Tags

(Today we have a guest article from Charles Tauber. I asked Charles to develop something he had written in the internal arts discussion board Rum Soaked Fist, as this is a topic not very much written about and should be interesting for Tai Chi enthusiasts. Please visit Charles Webpage where you can find his carpentry as Tai Chi rulers, guitars and more. // Thanks! – David )

By Charles Tauber / May, 2023

A basic guiding principle of the practice of Taijiquan is that the whole body is mobilized in movement, rather than isolated motion of the limbs. In Chen style Taijiquan, specifically, the method for uniting the body in motion is called “silk reeling” (chan si). As with most styles of Taijiquan, the specifics of practice vary between styles, within sub-styles and between teachers of the same style.

Early in their studies, most students of Chen Taijiquan are taught basic foundational exercises – called jibengong by some and silk reeling exercises by others – to assist with their understanding and development of the body method used in Chen Taijiquan. Much of the Chen style Taijiquan currently taught, directly, or indirectly, comes from Chen Fake (CFK), who is widely recognized as the most skilled Chen Taijiquan practitioner of the 1900’s. He left behind three best-known lineages of practitioners; family members in Chen Village, Feng Zhiqiang in Bejing and Hong Junsheng in Jinan.

Despite having a common source, there is considerable variation in how each of these lineages conceptualizes, teaches, and practices the art and its foundational exercises – jibengong/silk reeling exercises. One of the sources of variation is the result of Hong Junsheng, Chen Fake’s (CFK) longest-standing disciple, observing that CFK performed his movements one way in solo practice and another during application. With CFK’s approval, Hong altered how movements were performed in solo practice to be the same as how they were performed in application. Hong observed that to be martially effective, the movements needed to be performed in a specific way that is more strict than is generally required for solo practice. Hong called his resulting approach “Practical Method”.

In Chen Village solo practice, the elbows are often raised, and is a basic element of most solo practice, including foundational silk reeling exercises (chan si gong). Chen Xiaowang (CXW), for example, explicitly teaches that during an “outgoing” portion of a silk reeling circle “qi” travels from the abdomen (dantian) to the lower back (mingmen), up the back to the shoulder, to the elbow and then to the hand. Feng Zhiqiang’s training doesn’t explicitly teach this pathway but performs the circle similarly. By contrast, in Hong’s Practical Method, it is taught from the onset that raising the elbows is an error in any part of practice and is to be avoided from day one. In application, regardless of sub-style, the elbows are rarely raised since a raised elbow is a liability easily taken advantage of by an opponent or partner. One of the distinguishing characteristics between Hong’s method and that of Village/Feng is the use/non-use of the elbow in the pathway.

This leads to a second distinguishing characteristic. With Village/Feng solo silk reeling circles, and the dantian/mingmen/shoulder/elbow/hand sequence, the movement of the elbow precedes the movement of the hand. In Hong’s style, the hand precedes the elbow: the mantra is, “Out with the hand, in with the elbow”. In long weapons training – and some shorter weapons training, such as saber – the hand must precede the elbow: the weapon won’t work if the elbow leads. For example, if thrusting a spear outward, the forward hand leads the action, not the elbow. Similarly, when withdrawing the spear, the opposite occurs: the elbow leads the hand, pulling back with the elbow as the hand follows. In Village/Feng solo (empty hand) work, the elbow leads in outward-going movements while the hand leads on inward-going movements, the exact opposite of Practical Method. This has huge implications in how the solo movements – including the basic “silk reeling” circles – are performed and trained.

Another significant difference between Hong and Village/Feng methods is that in Hong’s method one shall not move the fulcrum during application. In practice, this means that one does not shift weight back and forth during application. In an art that relies heavily on leverage – “Four ounces deflects a thousand pounds” – shifting of one’s weight between legs introduces pushing or pulling that diminishes the effective leverage. In Village/Feng solo practice, there is a constant shifting of weight back and forth. (It is interesting to see video of Feng pushing hands where he does very little weight shift.)

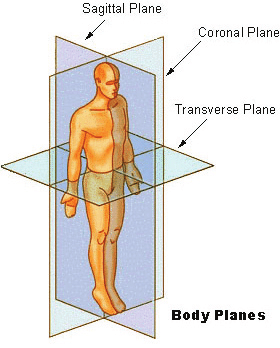

In the 1990’s, when CXW was travelling the world to give seminars, he explicitly taught that there is one foundational principle and three techniques for achieving that principle. The First Principle is that when one part of the body moves, the entire body moves, or put another way, when the dantian moves, the whole body moves. He taught that there are three techniques for achieving that. The first technique is to move the dantian left and right, that is, in a plane parallel to the front of the torso, i.e., the Coronal/Frontal plane. The second technique is to move the dantian forward and back, i.e., in the Sagittal plane. The third technique is any combination of the previous two, that is, movement of the dantian on any arbitrary plane.

CXW teaches movement of the dantian left and right using the common “arm circle” silk reeling exercise and its immediate variations. The arm circle exercise can be performed in two directions of rotation that he does not explicitly label. CXW teaches movement of the dantian forward and back using a single circling-of-the-wrists-against-the-abdomen exercise. That is the entirety of the silk reeling exercises he teaches, at least publicly: the arm circle, its variations, with and without stepping, and the wrist exercise.

By contrast, other Chen Village teachers do not teach this method. Zhu Tiancai, for example, does not explicitly teach it this way. He does, however, present something that CXW does not, the most common ways in which the arm circles can be combined, as seen in forms and applications. Zhu presents these in his 13-posture neigong set.

By contrast, Hong does not present or conceptualize movement this way: he does not breakdown three-dimensional movement into 2D (i.e., planar) motions. What he does do is present two – and only two – “3D circles” that form the basis for the entirety of the style, its solo work and applications. He explicitly distinguishes each direction of the circle, calling one “positive” and the other “negative”, terminology not used in other Chen variants. All solo forms are comprised of these two circles and/or portions thereof. (This is vaguely implied in Village presentations but left to the student to figure out, or not.) In Hong’s method, if one cannot identify at any place in any form or application which of the two circles are being performed, the action is being performed incorrectly. As in Zhu’s neigong set, there are eight most-common combinations of two circles with two arms, for example, both arms performing a positive circle, one are performing a positive circle while the other arm performs a negative circle, and so on.

In Feng’s teachings, none of the above is explicitly taught or stated: he, generally, did not break movement into 2D components, did not assign specific movements or actions to movement of the dantian (i.e., the basic arm circle being dantian moving left and right), did not teach that there are two and only two basic arm circles or that they could be combined to become the basis for all form and application movements.

One of the biggest differences between Feng’s silk reeling set and CXW’s silk reeling set is that Feng included many different actions with a wide variety of body parts, while CXW’s is almost entirely a presentation of the two basic circles with their variations. Feng included much more general training that includes things like striking with shoulders, elbows, back, chest, knees, forearm rubbing, grabbing, wrapping, punching, kicking, foot sweeps, and so on: its focus is much more along the lines of developing “the whole body is a fist”. In my opinion, Feng’s silk reeling set, along with his Hunyuan qigong set, are his primary contribution to Taijiquan. However, as Feng aged, he dramatically changed how he performed his solo work, including the silk reeling exercises, with much greater emphasis on health and longevity. He added more circles to movements, made the circles looser and less well-defined and introduced swaying back and forth and bending at the waist. Feng could instantly switch from large, ill-defined movement to effective martial application: astute students observed the difference between his solo practice and his application.

The preceding discussion only scratches the surface of what is similar and what is different between the most common variations of Chen style Taijiquan. As the old joke goes, “How many Taijiquan practitioners does it take to change a light bulb?” The answer is, “Ten. One to change the lightbulb and nine to say, “Oh, we do it differently in our school.””

A very good article. Thanks.

Chen Villagers, despite whatever wordings/translations they use, tend to use the same training methods, idiosyncratic focuses, etc., throughout the village, even though the members of the actual Chen clan will have some minor differences with some of the non-Chen members (like Zhu Tiancai, Wang Xian, Chen Qingzhou, etc.).

Hong Junsheng and Feng Zhiqiang were essentially outsiders to Chen Village, so their takes are interesting and illuminative, but they’re not definitive. Hong, not always in Beijing, studied off-and-on with Chen FaKe for a long time, but he was known for being sickly and not able to practice very hard. Feng Zhiqiang, whose main training was in Six Harmonies Xinyi, only studied with Chen FaKe maybe 3 to 3.5 years, despite his claims to have studied for 6-7 years (I had those years explained to me by a leading teacher from Chen Village). My point is that the movement styles of these two men do not necessarily reflect that actual Chen-style. In fact, the Hong-style of Taijiquan explicitly says that they do not move like the Chen style (they move “better”, of course).

Disregarding the Hong-style of Taijiquan as being “something else”, I think that Feng’s method of movement is worth examining because Feng had developed internal-strength skills in his Xinyi Liuhe and so he would see the Chens’ movement principles through knowledgeable eyes. One thing I notice about Feng’s movements is that he often uses the “seated on a stool” stance to do silkreeling, but the “seated on a stool” stance can be a horrible way to train a beginner in silkreeling movement: silkreeling movement starts from the feet, even though an advanced practitioner won’t overdo the feet/leg movements very much. A beginner who doesn’t know that silkreeling begins at the feet will go off on the wrong road.

2 cents